“Until the lions have their own histories, the history of the hunt will always glorify the hunter.” – African proverb, quoted by Chinua Achebe in “The Art of Fiction,” The Paris Review, no. 139

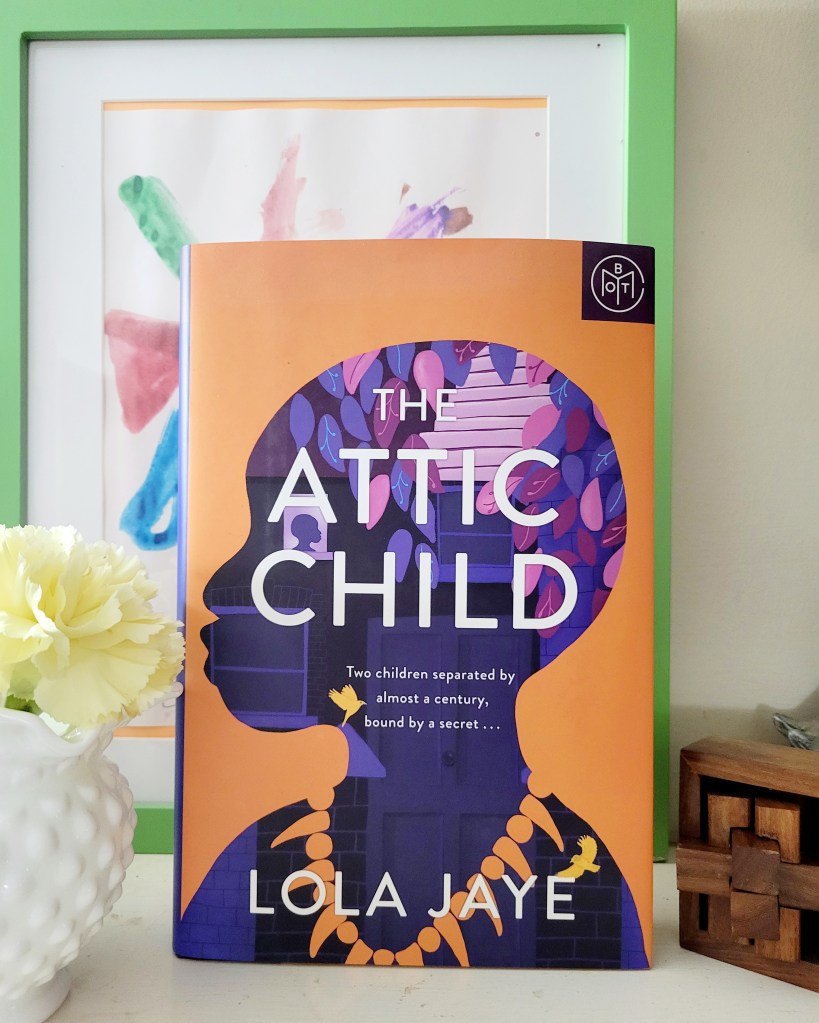

Lola Jaye writes in the author’s note of The Attic Child (William Morrow 2022) that the novel is her “attempt to give a lion a voice.” That lion is an African child sold to serve as a “companion” to a wealthy English explorer. While a work of fiction, The Attic Child is a reimaging of a real boy’s story – Ndugu M’Hali, a young African boy who was companion to Henry Morton Stanley until his death at age 12. The novel is a stolen and lost voice, but it’s also resilience, hope and love.

Dikembe, the youngest of his family, lives a sheltered existence, held tight to the breast of his mother and shielded from the horrors of King Leopold’s II colonization of the Congo until his father is killed for his resistance. To save him, his mother makes arrangements that he should join an English explorer, Sir Richard Babbington, as a companion. Dikembe believes it will be for no more than six weeks, and then he can return home to Africa. His gradual realization that he will never return home to his mother, that his mother is likely dead, is a bone-chilling ache of a read.

As Sir Richard’s companion, Dikembe is renamed Celestine and educated in the ways to be a proper English gentleman. To Sir Richard, he is a prized artifact from the Congo. He is paraded around at parties, forced to pose in ridiculous photographs, and treated as an example of how the “wild” Africans can be “tamed.” But he’s fed well. He has the finest of comforts and the best of tutors. A chasm builds in his heart as he is both Dikembe and Celestine. Then Sir Richard dies. The relatives who inherited the home strip Celestine of all the luxuries he’d grown accustomed to. As the only artifact they couldn’t profit from, they put him to work serving them hand and food. He’s kicked out of his plush bedroom and locked in the attic, where he hides his only prized possessions they haven’t taken; a doll given to him by his only friend and the bone necklace that had belonged to his father.

Several decades later, Lowra is locked in the same attic where she finds the necklace and doll. Her mother died when she was small and her father remarried her tutor, but only the tutor returned from the honeymoon. Left in her stepmother’s care, Lowra was repeatedly abused – beaten, starved, and left for days on end in the dark attic. She finally manages to escape. She’s worked with a psychiatrist and takes medications, but she’s just going through the motions of life – until her stepmother dies and she learns she has inherited the house, as it was her mother’s never her stepmother’s. Her only concern is for the necklace and doll, which remain in the attic where’d she’d left them when she fled.

Lowra’s true journey to healing begins as she becomes committed to finding out who hid the necklace and doll in the attic that had also been her prison.

Published months before Babel, The Attic Child has a comparable storyline; Celestine and Robin have very similar experiences, both being sold into the companionship of a wealthy Englishman and both rising to a rebellion. Unlike Babel, The Attic Child is solidly historical fiction. And it is cleverly and beautifully executed, with characters that breathe and sing. There’s hope and love and a voice.

Read this book.