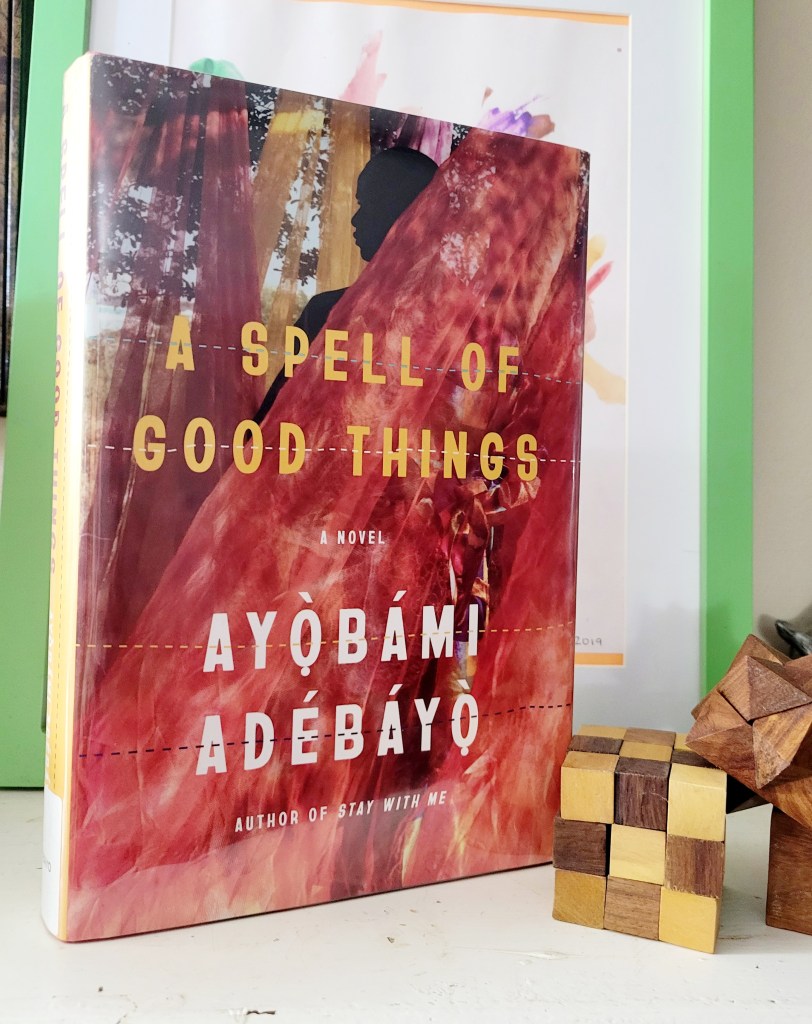

Booker season continues with Ayọ̀bámi Adébáyọ̀ ’s A Spell of Good Things (Knopf 2023). The novel is Wole Soyinka (without the bitter wit) meets The Girl with the Louding Voice – full of political corruption, a hunger for both food and education, and a sharp division between classes while still showing, quite literally, that we all bruise the same. It was just another okay read – there were many suitable and more worthy publications from the past year for the longlist, but no one asked me to be a judge. *Shrugs*

The novel alternates between Eniola and Wuralola. Eniola is a school boy who works for a tailor, shows his elders respect, and is just waiting for his father to get another job so that he can go to a better school and his family can return to the good life they had when his father’s role as a history teacher was respected by the government. Now, Eniola is hungry more often than not. He is mocked by his classmates. He is beaten by the school administration because his family cannot pay the tuition on time. He takes his licks without a word, but his younger sister, Busola, a highly intelligent and talented young woman, is quite vocal about the unfair turn her life has taken. After being forced to beg for money, Eniola has an opportunity thrown in his lap; it’s for a corrupt politician, but the money is more than enough for school, food, and even a surprise for Busola.

Wuralola is a child of privilege. Given every opportunity growing up, she’s now a doctor in her first year of practice. She’s working herself to the bone, realizing that life isn’t quite what she thought it would be and wondering if she’s the sort who will simply never be satisfied. Her boyfriend and eventual fiancé, Kunle, is the abusive son of a wealthy man with political aspirations.

Wuralola is losing weight due to stress, the workload at the hospital, pressures by her family, and the increasing violence of the man who swears he loves her. Eniola is losing weight because there is no money to buy any food for his family of four. The use of food is the main way the disparity between the two classes is presented; Wuralola’s hunger is readily fed, whereas Eniola’s is an ache that won’t quit.

The two worlds come crashing together with fatal consequences when Wuralola’s soon-to-be father-in-law announces he is running against Eniola’s new benefactor/boss. Political corruptness will destroy them both. There’s little new or exciting about this novel. Some of the best sections come from secondary characters like Eniola’s and Wuralola’s mothers and those are brief snippets. The switching between Wuralola and Eniola is structured strangely such that by the time you get invested in one story, you’re tossed back in the one you’d already forgotten about. By the end, I was so far removed from the novel and just ready to reach the conclusion.

This may be a harsh review, but it’s not a bad book and I ultimately rated it well. But why, you ask? Because I don’t understand how it was selected for the longlist. It’s perfectly okay, but one of the best books of the year? I just don’t see it, despite it being perfectly fine.

Booker count: 3 of 13

**One of the 2023 judges is a Shakespeare scholar. I’ve decided to keep track of the novels that name drop Willy Shakespeare or his works. This one drops Hamlet, and it’s 3 for 3.