“Maybe we’re all obituary writers. And our job is to write the best story we can now.”

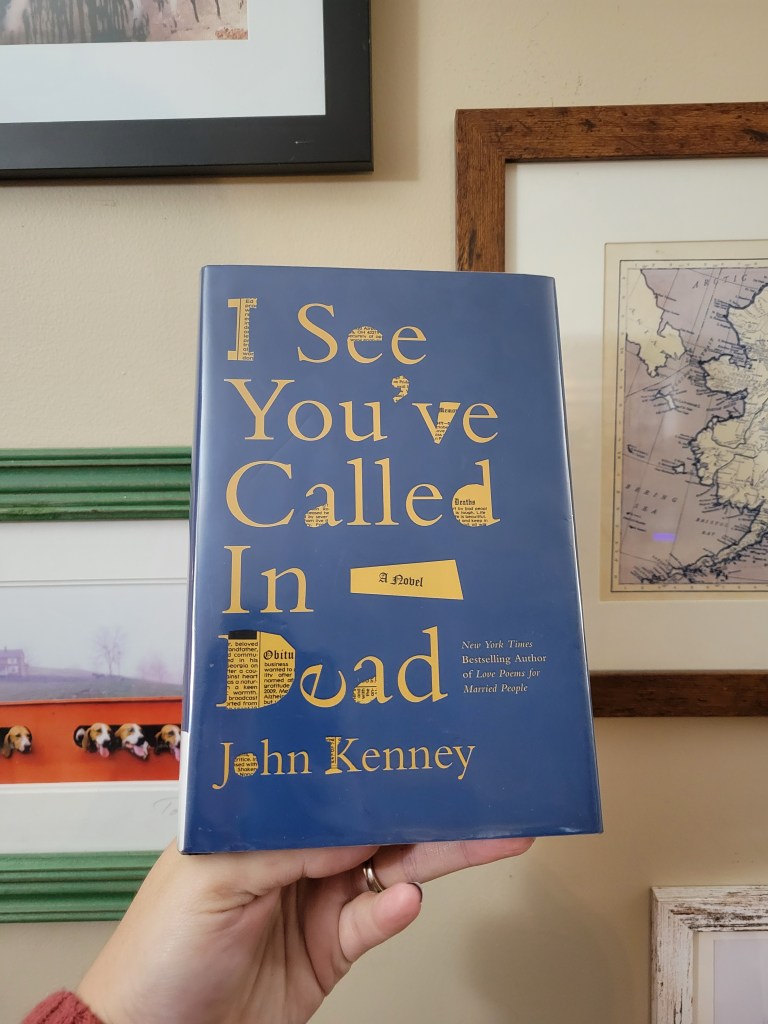

@rolly.looks.at.books recommended John Kenney’s I See You’ve Called in Dead (Zibby Publishing 2025), and when the world’s most well-read bichon recommends something, you listen. It’s quirky, hilarious, and full of heart. I can see why it draws comparisons to Backman’s A Man Called Ove with its loveable, quirky cast and ruminations on death (and what it means to be alive.)

Bud is a 44-year-old obituary writer. His wife left him, and he’s just going through the motions. (He’s also about to be the age his mom was when she died.) He used to be good at his job, but not anymore – the obituaries he writes just a fill the blank where he often gets the information wrong. He gets drunk one night, accesses the database, and writes his own obituary – a hilarious self-depreciating one – that he publishes worldwide. He immediately gets suspended with pay pending a hearing. Everyone thinks he’s dead. “I got better,” he says. They can’t fire him because he’s dead in the system, and they have to figure out how to convince a computer he’s alive. (Hey – don’t fire the folks who make mistakes but also bake brownies and remember birthdays and can make sure a person isn’t dead in HR.)

The reader realizes pretty quickly what’s coming – Bud is going to face a death that will mark him forever, and in doing so, he learns to live. Oh, it’s a kick in the teeth you see coming from miles away but every line leading up to that moment is worth it.

Bud starts going to funerals of people he doesn’t know after meeting a girl at the funeral for his ex-mother-in-law. He takes his friend, Tim, with him. Slowly he introduces us to Tim and their relationship. (You will love Tim, which is the point.) We also meet Leo, the 7 almost 8-year-old neighbor, and Clara, the woman from the funeral. We see their traumas and how they all deal with death and living and grief and happiness.

Kenney was inspired to write this novel after his brother passed from pancreatic cancer. What he captures in his author’s note is his brother’s humor even in being terminal. That humor in what is a dark subject matter is what makes this book so much of a heart hug.

This year, I turned 43. My father was 43 when he died. To say it’s not something I’ve thought about at length would be a lie. I connected to this book in both expected and unexpected ways – it’s a special one, for sure.

Read this book.