The Crane Wife is a Japanese folktale wherein a man saves a wounded crane, and the crane returns as a beautiful woman. The man is poor, and the crane weaves her own feathers into beautiful garments that are sold for large sums. The woman is becoming increasingly ill as she is using her own feathers and flesh to make the materials. When the man sneaks upon her and realizes that his wife is the crane, she flies away – leaving him with a broken heart.

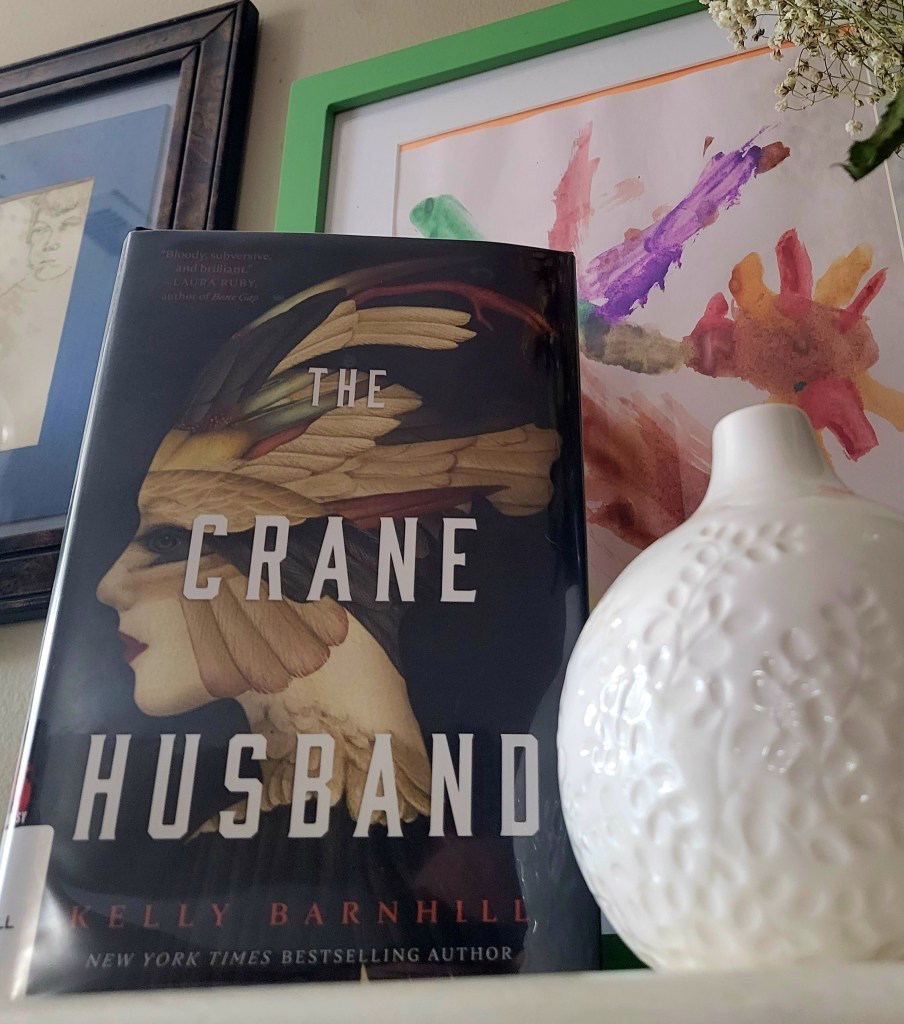

Kelly Barnhill gives us a masterful retelling of this folktale in her The Crane Husband (Tor 2023). This slim reimagining places this well-known folktale squarely in modern day Midwest America. Narrated by an unnamed 15 year old girl, The Crane Husband echoes many of the themes of Barnhill’s When Women Were Dragons.

“On the farm,” she said quietly, “mothers fly away like migrating birds. And fathers die too young. This is why farmers have daughters. To keep things going in the meantime, until it’s our time to grow wings. Go soaring away across the sky.”

After the narrator’s father dies, her artistic mother becomes more eccentric. When she finds a guy with a broken arm in the sheep pen, their world changes. A large crane shows up when the man leaves, and her mother has told them to call him Father. Our narrator refuses. Her mother stops eating, stops caring for the sheep, stops making cheese, and stops selling her art. She spends waking moment with the crane. She tells her daughter that love is enough, and they don’t need money. Her body becomes more bloodied and broken with each passing day.

Barnhill turns the folktale on its head while retaining much of its heartbreak; the lessons remain the same.

Barnhill is a master storyteller, and her efforts are very much on display in this small novel. This is a folktale, not a fairytale, and the endings of folktales are seldom happy. The Crane Husband is a haunting nightmare for our narrator and her young brother, and its ending is one of resilience not happiness. There’s a lot of similar imagery and phrasing between this and When Women Were Dragons – both with the idea of flying away (birds this time, not dragons) and with knots to stay grounded – but it’s a retelling that stands on its own.

Should you read this? Absolutely.