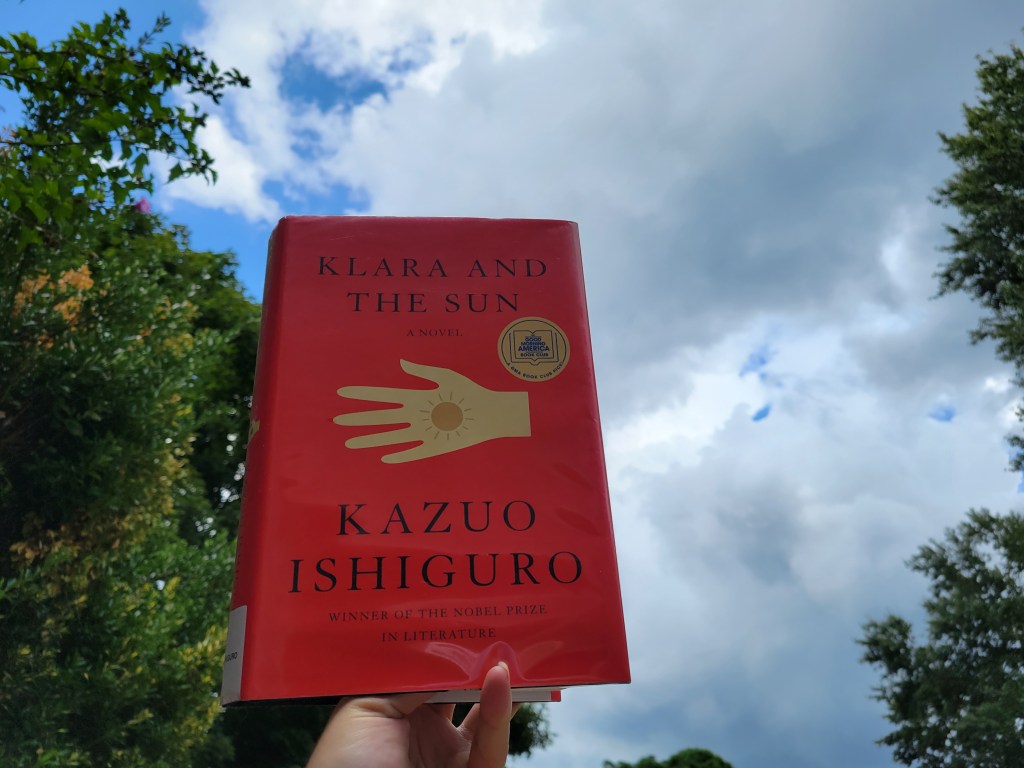

Kazuo Ishiguro may be the odds-on favorite for the 2021 Booker Prize, and understandably so. Not only is he a previous winner (Remains of the Day 1989), he is arguably one of the most heralded contemporary English authors. I don’t think anyone was surprised to see Klara and the Sun (Knopf 2021) make an appearance on the longlist. I read and loved Remains of the Day decades ago, so I was looking forward to this one.

I don’t know what I was expecting, but it wasn’t Dystopian Science Fiction. And what a fun surprise that was. If you want to be surprised, stop reading now. There will be some spoilers.

Klara is an AF, Artificial Friend, designed to entertain and keep children from becoming lonely. These robots are made to look like children and come in various models, each fed by the Sun. The novel opens in the AF store, where the reader is introduced to other AFs and the Manager all through Klara’s observant eyes. This tunnel vision approach, also used in Remains of the Day, has been criticized by some, but the novel wouldn’t have been nearly as successful without it.

Klara is purchased to be the companion of Josie, a “lifted” but sick girl. The wealthy have been able to “lift” their children – genetically editing them to make them smarter and more likely to succeed. It’s a dangerous process not without risks, and the reason for Josie’s illness and the death of Josie’s sister.

Klara is purchased as a friend and companion. Josie’s mother has other, ethically questionable, intentions – a plan born of guilt and desperation. Klara understands her assignment, and she also understands what Josie’s mother wants of her. But Klara is no normal AF – and she resolves to save her Josie by calling on the Sun to heal her.

Klara and the world of AFs immediately called to mind the 1980s sitcom Small Wonder and Vicki; however, the sitcom was lighthearted and full of warmth, and the ending of Klara and the Sun was a more realistic twist of the knife in my gut. The first-person narration and Klara’s unreliable tunnel vision made it all the more impactful.

It’s not my personal favorite of the longlist, but gosh it’s certainly worthy.

Read this book.