“… because their parents no doubt told them I was and was not to blame and so why go into a past where nothing and no one can be reclaimed…”

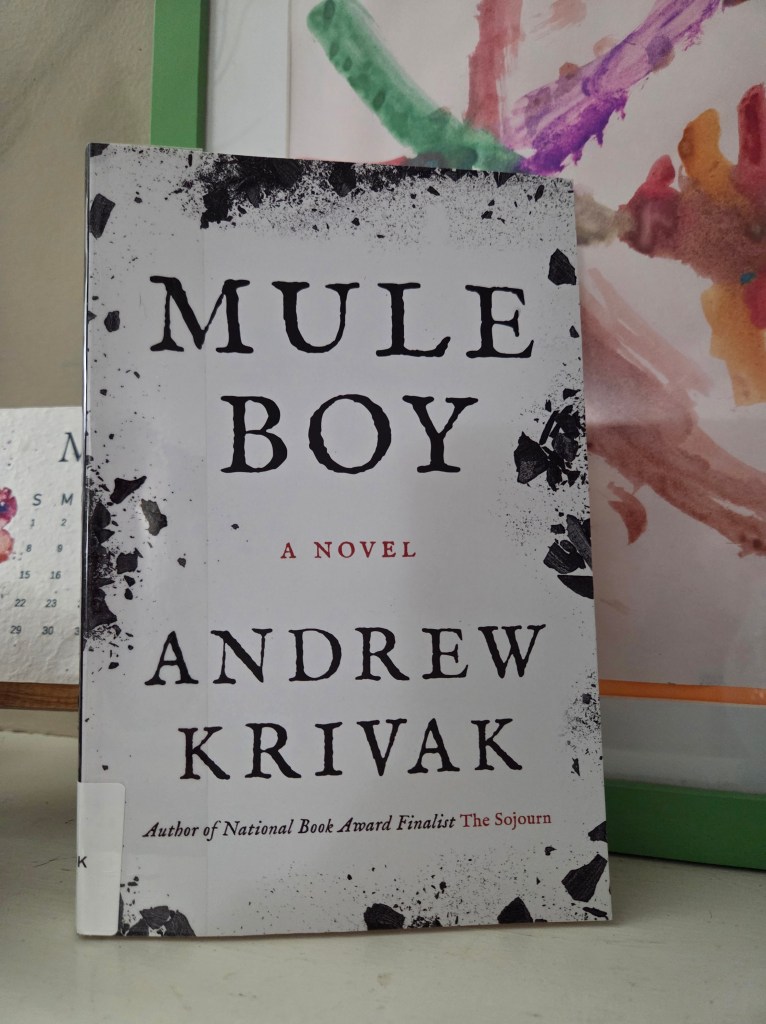

Andrew Krivak’s Mule Boy (Bellevue Literary Press 2026) is a marvel, and it will undoubtedly be in my top reads of the year. Possibly of the decade. I don’t think there are current plans for publication in the UK, so it is not Booker eligible. Pity. This book drips Booker type. Told in incantatory prose, Mule Boy is one long sentence, a story rising on the raged breath of memory and falling like a prayer or a poem on the reader – a chant of fear, forgiveness and guilt wrapped into a memento mori. I loved every last bit of it.

In 1929, 13-year-old Ondro Prach begins a new job as mule boy. He is no stranger to the danger in the mines, but he and his mother need the money. The mule is named Wicked, and Ondro speaks to him in Slavic and gives him carrots. He earns not only the trust and respect of the mule, but of the four miners he works closely with. When disaster strikes, Ondro is the only one to walk out alive. “Just the mule boy,” they say to the wails of family.

Survivor’s guilt and memories of what happened when he was trapped in the mine with the dying men haunt Ondro throughout his life. When he is jailed after refusing to fight in the war, he meets a man who helps him process his memories and his life – a man who also secures his release from jail – with Ondro ultimately serving out his sentence as a ranger. Over the years, the family members of the dead seek him out. They want his memories. They want the last moments, last words. And Ondro gives them what they seek – the truth. Ondro is waiting for one woman, though, to show up at his door. The one he loves and who once loved him. The daughter of a miner.

Ondro is a fascinating character. The son of immigrants, survivor of a mine disaster, conscientious objector, reader of Shakespeare and a Hebrew scholar, he is multi-faceted and so masterfully depicted. And the writing thrums just under your skin – lulling, cajoling and hypnotic. And oh so alive.

Read this book.