“Long ago. Saying those words puts me in a strong mood. Long ago – what does that mean? I’m not all that young, but I’m not that old either.”

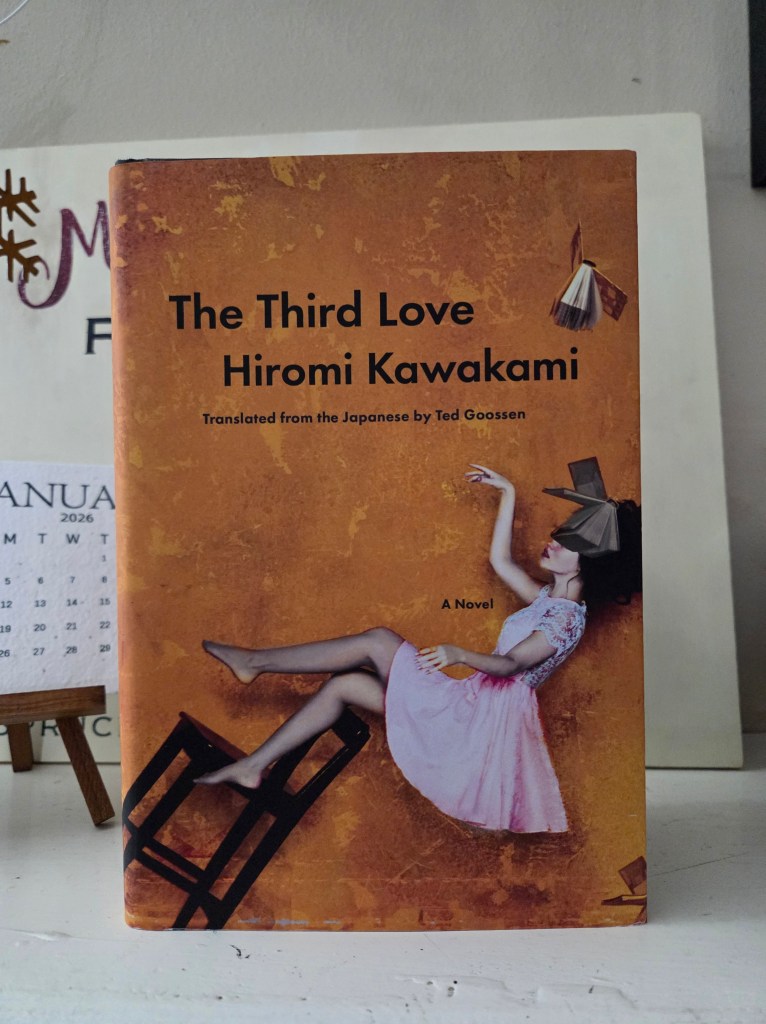

I’ve been meaning to read more works in translations outside of my read the world challenge, and Hiromi Kawakami’s The Third Love (translated from the Japanese by Ted Gooseen) (Soft Skull Press 2025) fit that bill. (A huge thanks to the publisher for the finished copy!)

I’m not the biggest fan of time-bending/time travel novels, but the dream travel utilized here works extremely well.

Riko, a modern woman, fell in love with the man she’d marry when she was a toddler. She ultimately married him, but all that glittered wasn’t exactly gold; the marriage is marked by infidelity that he is not even ashamed of. When she reconnects with the janitor for her elementary school, Riko learns magic. She escapes her modern life and unhappy marriage by traveling back in time – first, she finds herself as a high-ranking courtesan in the seventeenth century and then as a serving lady to a princess in the Middle Ages. The different lives and worlds she finds herself center heavily on traditional Japanese literature and legend. While I wish I had a stronger foundation (I have The Tale of Genji, but I’ve never read it), such background isn’t necessary to enjoy the worlds Kawakami has given the reader.

As Riko dream travels, she is able to draw parallels between the lives she’s joined, Japanese literature, and her present life and relationships. The novel takes an open look at the role of women across centuries, especially as related to sex, child-rearing, motherhood, and love in general.

It’s certainly worth adding to your stacks.