“What did she mean with not very dangerous? ‘Mais faites attention aux requins-marteaux.’ Pay attention to the what now”

The Sex Lives of Cannibals: Adrift in the Equatorial Pacific (2004) and Getting Stoned with Savages: A Trip Through the Islands of Fiji and Vanuatu (2006) have long been my go-to recommendations for self-deprecating but insanely funny travel writing. When asked what author I wanted to have a drink with, I’d always answer “J. Marteen Troost.” If I’d only known then.

When Lost on Planet China: One Man’s Attempt to Understand the World’s Most Mystifying Nation (2009) was published, I was giddy. I love Troost. I love Asia. What could possibly go wrong? Turns out, everything. I hated it. Troost came across as a culturally insensitive, white privileged man upset at the world. I renamed it : “SOS – Lost on Planet China – The Story of One Man Bitching and Moaning his Way Across the World’s Most Mystifying Nation” in my review (which you can find in the archives!). His next book was supposed to be about India, and he claimed to have loved India. (He’d hated China.) The book about India never came; instead, he revisited the South Seas. With Headhunters on My Doorstep: A True Treasure Island Ghost Story (2013) considered the final installment of the South Seas trilogy, we both agreed to forget about China and the never published book about India. Well, sort of.

Hand to page, I almost DNF’d at about 50 pages in. This was not the Troost I loved. This was more the Troost that had been lost in China – only this time he was sober and bitter. Troost’s alcoholism and fall from grace come at the reader with solid punches as he attempts to follow in the footsteps of Robert Louis Stevenson. This journey may have taken place at his beloved South Seas, but it really was a self-journey. As such, the blurb and the cover had set him up to set me up for disappointment. But I kept reading.

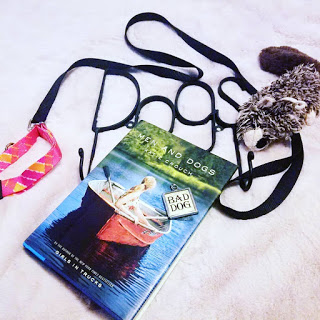

The self-deprecating humor is pathetic this time, not comical, but there are glimmers of the Troost who tagged along with his girlfriend so many years ago. When he talks about the islands, the views, the water, the people – you can see the smile on his face. Even when the half wild dogs that belong to everyone and no one nip at his heels as he’s running. And that is his magic.

The book about India will likely never happen due to Random House pulling the plug on the contract and demanding the advance back while still holding tight to the work he’d created. I’m not going to get into the legalese of it, but he was screwed. And not in the good way. Is that why he drank? No. But it certainly caused a crisis of faith that had him returning to vodka and eventually resulted in him being broke and on the verge of losing his family to the drink. So, he quit.

This trip to his beloved islands was during the first year of sobriety. Troost himself is the ghost and this is his story.

I’m glad I didn’t stop reading. Does it give me the same joy as the first two? No. But I respect it. I respect and applaud his journey. May he find his voice again. And the joy. And give swimming with sharks another go.