PJ pet the cat in his lap. “Well, I think in his past life, Pancakes was a goat herder in Mongolia. And I believe I was one of his goats.”

“A goat?” Ollie asked, laughing. “You think you were a goat?”

“Yep. Or perhaps a yak. But Pancakes and I found each other again, in this life, which is a beautiful thing.”

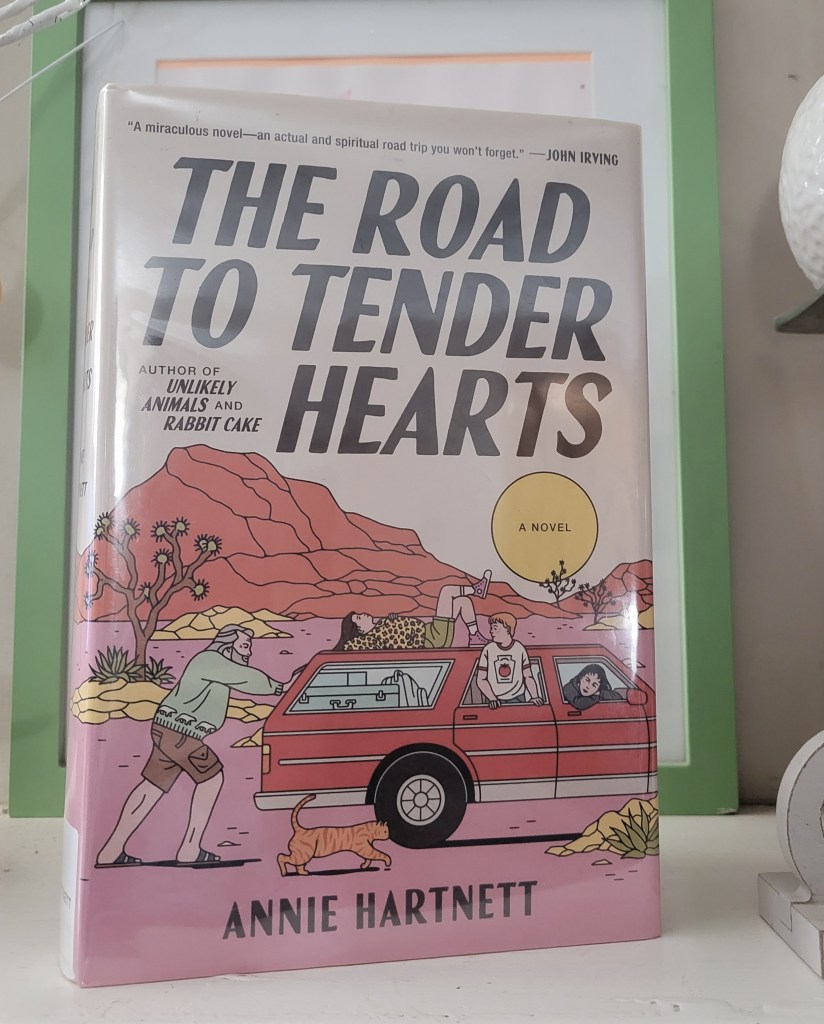

Annie Hartnett’s Unlikely Animals was one of my top reads of 2022, and I was hoping The Road to Tender Hearts (Ballantine Books 2025) could bottle some of that same magic. Spoiler – it can and it very much does. Hartnett’s writing is a hug with teeth – a lot like life. Unlikely Animals said something akin to the stories we like best are “both funny and sad,” and this one hits that mark.

Pancakes is an orange tabby that moonlights as the grim reaper. He was happily living at the nursing home in Pondville, Massachusetts, until the director noticed his unique talents and felt he was paying a bit too much attention to him. He took the cat to the shelter. He still died, of course, because Pancakes doesn’t miss.

The cat ends up on a road trip with PJ, an alcoholic manchild who is struggling with a powerful grief, and Irish twin siblings, Ollie and Luna. Ollie and Luna are orphaned (pretty horrifically) and are the grandchildren of PJ’s estranged older brother. Child services figures since PJ’s a living relative right in town, he’s better than foster home. PJ was unaware they existed, but just like he couldn’t let Pancakes go back to the shelter, he can’t let them go to a foster home, so he decides to take them on his road trip to visit his recently widowed high school sweetheart who lives at the Tender Hearts Retirement Home in Arizona. His daughter, not on the best terms with her dad, joins because she’s unemployed and she knows that man cannot be trusted to watch children. Or a cat.

It’s a gritty and hard to pin down novel – one that is so full of heart and so delightfully bizarre. There are ghosts and lollipop trees, talking cats and hats, a mermaid, vultures who sing out for two children to stay alive, near misses, Abe Lincoln’s stolen arm, and a lot of death. You’ll fall in love with this hodge podge group of misfits on a journey to love, forgiveness, second chances, and hope. And yes, you’ll even love the harbinger of death, Pancakes.

Read this book.