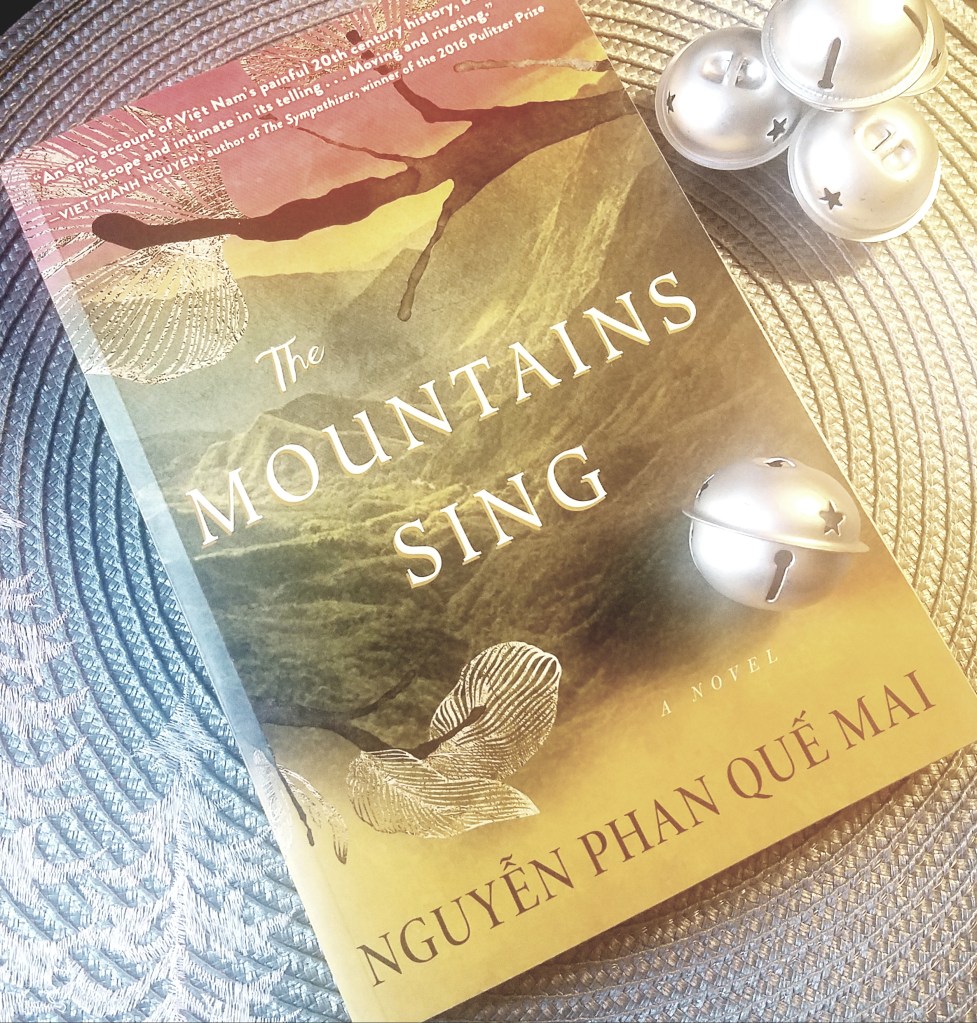

It truly has been the season of “women at war” books for this booknerd. After I left Korea, I went to Vietnam and a family saga that spans decades of turmoil. The Mountains Sing (Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill, 2020) is Nguyễn Phan Quế Mai’s first novel in English. A celebrated poet, Mai’s language purrs on each and every page of this beautiful novel. (I have posted previously about the questionable manner in which I found myself with an ARC of this novel. For these purposes, I’ll just reiterate that one should not sell ARCs, and I should have paid better attention to my purchase.)

The Mountains Sing is a complicated story set in a complicated country. Set primarily against a backdrop of the Việt Nam War, the novel of the Trân family also touches on the Japanese invasion of Vietnam, which was followed by the Great Hunger and the Land Reform – a tumultuous history that defined every member of the Trân family.

Despite jumping around in the chronology, the novel centers around young Huong. Both of Huong’s parents have joined the war effort – her father as a soldier and her mother as a doctor. She lives with her maternal grandmother, Grandma Dieu Lan, a teacher by trade, in a beautiful house in Ha Noi. Within pages of the novel opening, the sirens alert the residents that the American bombers are approaching and they must take shelter. Huong’s grandmother yells at the mothers and children who are trying to find unoccupied bomb shelters to go to the school because they certainly wouldn’t bomb a school. Huong and her grandmother survive the bombing, but bodies and parts of bodies litter the streets as they hurry home. After months of quiet and relative peace, war has returned to Ha Noi.

As the story unfolds, we learn more about Huong’s grandmother, the daughter of wealthy landowners, and the deaths of her parents in the wake of the Japanese invasion followed by the Great Hunger. Through her stories told to Huong, we learn of Wicked Ghost and the horrors he inflicted on her family. We learn of the difficult choices Dieu Lan makes when she is forced to flee her home with all but one of her children during the Land Reform. And we see the lasting impacts of those choices on her now grown children.

The Mountains Sing is about mothers and the ties that bind. It’s about home and family. The writing is poetic and beautiful, and that gorgeous writing style is what allows the light and hope to glitter in this story that is so full of war, death, and destruction. I did find the pacing in the last fourth of the novel to be unpleasantly rushed as Mai attempted to tie up any loose ends. It was a disservice to an otherwise gorgeous novel to vomit out the ending in such a hurried and uncontrolled way; however, I still strongly recommend this novel. I can’t emphasis enough the importance of books like this and voices like Mai’s.

Read this book.